By P. Monte Lawton

—–

From Bad river’s mouth twelve miles will bring

Us to the place Che-as-sin-ing;

In the language of the Chippewa race,

Its meaning is the Big Rock’s Place.

—–

Albert Miller, 1890

As a child growing up in Chesaning, the author often wondered about the history of the Big Rock, a local landmark. The name “Chesaning” comes from the Anishinaabemowin words “Chi-Asin”, which means “Big Rock.” Attending Big Rock Elementary School brought students frequently into view of the geological anomaly. Daring children would often climb the rock during recess and after school, often to the concern of parents and teachers. Robert Lawton, the author’s grandfather, also remembers the rock as a fixture of the community. As a child, Bob would often go with friends to climb the big rock, and some would carve their initials into the stone (Personal Communication, 2014).

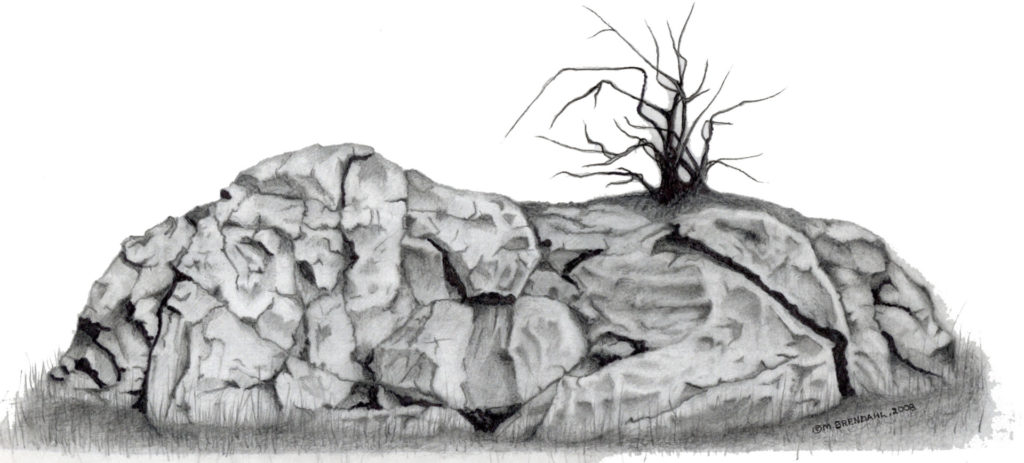

The rock is quite large, setting roughly 2 meters in height and covering 10 meters in diameter above ground. Many elderly community members remember the rock as being larger. Based on historical photographs, the rock appears to be sinking into the fine grained lake plain soils. Still there to this day, the igneous formation is located in the northwestern quarter of Section 15, Chesaning Township.

Chesaning is a small agricultural community in the southern extent of the Saginaw Valley, which sets to the south and west of the Saginaw Bay, Michigan. The town exists along the southernmost central portion of Saginaw County, halved east-west by the Shiawassee River. The Shiawassee is one of the few rivers in Michigan that run south to north, and certainly the longest to do so. The banks of the river are very high through Chesaning, reaching 15 to 40 feet in height. Traversing the surrounding area are many, almost parallel streams east and west of the Shiawassee River. Seasonal flooding, especially during the spring, made canoe the only method of transportation for long periods of time (Leeson and Clarke, 188 l ). The areas around these streams traditionally became occupied during the winters by local Ojibway and Ottawa, when the larger groups split off into three-family-groups (Ireland, 1966).

Chesaning lies in the heart of the Great Lakes within the former proglacial Lake Saginaw. The fertile lake plain soils are gravelly, sandy loams, mottled with patches of clayey loam (Leeson and Clarke, 1881). The most recent glaciers left the region ten thousand years ago, though several testaments to their legacy remain behind. Saginaw County is an especially flat, topographically monotonous part of Michigan. It is also the only county in the state to have no naturally-formed lakes. Therefore, any geological deposits of significant character or size are very recognizable. A couple of these had some ritual significance among peoples inhabiting this part of Michigan. The Big Rock was one of these; a ceremonial meeting place of Ojibway and Ottawa peoples.

The landmark in Section 15 is referred to as, “the lone rock in the woods,” by historical sources. Ironically, the rock is not alone when it comes to local contenders for the name of “the big rock.” James Cook Mills, writing in 1918, relates a debate surrounding the location and description of this ritual and ceremonial feature:

“[the other] rock was long ago blasted in pieces by the early white settlers and burned into lime. The name of the village and township was undoubtedly derived from the ‘lone rock’ in the woods, for the reason that the name was not applied until after the stone in the river had entirely disappeared, though ‘Totush,’ an Indian who died in the neighborhood about 1840, declared that the latter should have the honor (Mills, 1918).”

As Mills says, there was another “big rock” known in the area; the rock in the river. Ironically, the location described is only a mile or less from the “lone rock;” across the river from the settlement of Wellington Chapman (Mills, 1918). Mr. Chapman was the first settler to farm in the area, and his plot occupied the southeastern quarter of Section 16. Local narratives state that there was an “Indian com field” maintained here since the 17 century (Leeson and Clarke, 1881). George W. Chapman, Wellington’s brother, purchased the land adjacent to him, consisting of the northeast quarter of section 21. They each purchased their farms in 1841, paying five dollars an acre. George’s plot contained a planted “Indian orchard” of about twenty-five fruit trees that was said to have existed since the l 760’s (Leeson and Clarke, 1881).

Mills affirms that the “lonely rock” to “undoubtedly” be the one for which the area and township are named. The language reads as presumptuous, and Mr. Mills’ reason is lacking in substance. Names persist, even when their namesakes have died or passed out of memory. This brings to life Reginald Bolton’s observation that, “These Indian names often tell us something of the features of a place which may have disappeared long ago (Bolton, 1972).” Mr. Bolton understands this post-contact transformation better than most; he studied the prehistory of New York City.

The Rock in the river would have been the more noticeable of the two landmarks, as the river was a resource as well as a transportation network. This lime-rock is also mentioned in Virgil J. Vogel’s Indian Names in Michigan. An interview with Eli Thomas of the Isabella reserve reported that the feature was “an object of veneration to the Indians (Vogel, 1986).” The native sources, Totush and Thomas, agree on which rock was the original namesake, however, many historical sources seem unaware of “the rock in the river”. Instead, they fail to mention this lime-rock at all, calling the “lonely rock” in Section 15 the “big rock.”

Who Lived at The Big Rock in the River?

Based on historical narratives, it can be established that the Big Rock was a meeting place and navigation reference for quite some time. The Shiawassee river existed as a magnet for human activity itself, especially on this particular stretch (Fred Dustin, 1930). Many different native peoples are believed to have populated this area throughout history; the Pottawatomie and Miami driven from the south, the Ottawa from the east, and Haudenosaunee (Iroquoian) speakers. However, the group that truly made their homes here during the 18th and 19th centuries were the Ojibway (or Chippewa). The Ojibway were driven from this region along the Shiawassee, perhaps many times, but they always returned. Many still occupied the region when white settlers first arrived in the early 19 century (Ireland, 1966).

According to an interview with Chief Okemos in 1873, a native by the name of Noc-chic-o-mi lived with his two children at “the Big Rock, on the Shiawassee, called Chesaning (Webber, 1895)” during the time of the 1819 treaty. Noc-chic-o-mi later moved up to Saginaw and became chief of the tribe. It can be discerned that when new lands further north were established for the Saginaw Ojibway, many moved there. On their heels were the first wave of Euroamerican settlers.

“The War of 1812… gave the U.S. the prestige and power to seek and secure further territory for the increasing flow of emigrants moving from East to West (Ireland, 1966).” The treaty of 1834 established land in present-day Isabella County for the settlement of Native peoples still living on the Big Rock Reserve. By 1837 the Big Rock Reserve had been officially closed, opening the space for land sales.

In 1839 a white man named Thomas Wright began squatting there with his wife and two children, subsisting off of trapping, fishing, hunting, and bartering with natives. The place that would become Chesaning was so far from contemporary Euroamerican settlements that his wife went two years without seeing a white woman. Coming up the Shiawassee River in 1841, the Chapman brothers found the Wright family living in a crude log cabin on the property the brothers had purchased (Mills, 1918).

It is not clear how the brothers took this news, though it is noted that Wright eventually resettled on the southeastern quarter of section 16 in some fractional piece. Little else is known of Wright, beyond that he served as postmaster for Chesaning for some time, beginning 1846 (Romig, 1973). The place of his cabin is the precise place where Wellington Chapman built his home, overlooking the Rock in the River (Mills, 1918).

Who Destroyed The Rock?

Historical records suggest that the rock was removed after 1841, as Wellington Chapman constructed his house overlooking the feature in that year (Leeson and Clarke, 1881). The landmark probably did not last long after people began navigating the river and building lumber mills. “The Owosso & Saginaw Navigation Company was incorporated … March 21, 1837,” its mission; to make the Shiawassee navigable from Owosso to Saginaw. The company began work the same year, “removing fallen timber, driftwood, and other obstructions (principally between Chesaning and the mouth of[the] Bad river) (Michigan Historical Publishers Association, 1982).” These “other obstructions” may have included the large lime-rock formation in the river bed.

Supporting this narrative of the boulder as an obstruction are the recorded testaments of early settlers that one or two barges were wrecked on the Rock in the River (Ireland, 1966). The goals of the Owosso & Saginaw Navigation Company were to make Owosso more accessible in hopes of developing the village into a city (Michigan Historical Publishers Association, 1982). Likely, no one on the planning board considered the Indian ceremonial object; the native population had largely left the area for new reservations (reestablished in the 1834 treaty) by this time.

According to Mark Ireland, “all the records available for information [indicate] that [the] original limestone rock in the river was blasted out in order to build a dam for the first saw mill, erected in 1842, by the owners, North, Ferguson, and Watkins.” It has also been generally understood by local historians that the mill owners and other citizens of the village agreed that henceforth the traditional history and name should be transferred to the other large rock in the woods nearby (Ireland, 1966). This would explain why even many of the oldest living members of the community have never heard of the lime-rock.

When was the Big Rock Destroyed?

The documented testament of an old resident suggests the rock was still intact when he arrived in 1851. His narrative places the blasting of the rock just a few years after this, which flies in the face of other evidence. The Owosso and Saginaw Navigation Company formed in 1837, and finished their work by 1846. It can be assumed that they would not have left such an “obstruction” in the path of the flat bottomed barges used at the time. Additionally, as several mills were constructed along this section of the river, the temptation to control the path of the water would have been too great. Perhaps by cross-referencing some of these mills, their owners, and their time of installation, more can be learned about the timeline of Chesaning settlement and the rock itself.

The name, “Big Rock,” likely applied to both formations, and each saw many com feasts and ceremonies (Ireland, 1966). Such geological structures would have stood out to peoples in the area, especially in the flat, unchanging Saginaw Valley. Both were certainly geographic land-markers, though the rock in the river was probably more recognized, as this particular location was highly used by natives for resource procurement and travel (Leeson and Clarke, 1881). In support of this, there is evidence to establish that Chesaning was a sizable late pre-contact Indian settlement. In fact, a 1816 canoe journey by a Henry Borleiu up the Shiawassee (presumably from Saginaw) reported that Chesaning “was much the largest” village of three he found along the river (Michigan Historical Publishers Association, 1982). When Mark Ireland published his book in 1966, Saginaw County had the second most sites in the state, with 158.

Many of these were logged by Fred Dustin who lived near present day Bridgeport. Dustin was a pioneer in Michigan Archaeology despite never attaining a high school education. His work includes analysis on the pipe bowls, ceramics, and food storage of the Ottawa and Ojibway inhabitants of the Saginaw Bay region. Through grant funded research Dustin provided a wealth of information on the indigenous people who survived and even flourished at times in a harsh, seasonally temperamental environment. He is also responsible for a written account of the 1819 treaty between the Saginaw Ojibway and Lewis Cass. It would be an understatement to say Fred Dustin has made a contribution to the Archaeology and History of the Great Lakes. Generations of archaeologists (both academically credentialed and avocational) have completed work in the Saginaw Valley, reconstructing the lifeways of those who came before European settlement. There are now approximately 1450 documented archaeological sites in Saginaw County. The majority of these sites were reported by farmers, construction crews, and archaeologists who were never trained in a university setting. Present day archaeologists still benefit substantially from these individuals and the information that they have collected.

References

Bolton, Reginald Pelham. Indian Life of Long Ago in the City of New York. New York: Harmony, 1972. Print.

Dustin, Fred. Some Ancient Indian Village Sites in Saginaw County, Michigan. S.l.: S.n., 1930. Print.

Ireland, Mark Lorin., and Irma Thompson Ireland. Place of the Big Rock: Chesaning, Michigan, 1842-1950. Chesaning, MI: Chesaning Public Library, 1966. Print.

Leeson, M.A., and Damon Clarke. History of Saginaw County, Michigan. Chicago: C.C. Chapman&, 1881. Print.

Miller, Albert. “Rivers of the Saginaw Valley.” Michigan Historical Collections. Vol. 14. Lansing: Darius D. Thorp, 1890. 505. Print.

Mills, James Cooke. History of Saginaw County, Michigan; Historical, Commercial, Biographical. Saginaw, MI: Seemann & Peters, 1918. Print.

Romig, Walter. Michigan Place Names: The History of the Founding and the Naming of More than Five Thousand past and Present Michigan Communities. Grosse Pointe, MI: Walter Romig, 1973. Print.

The Michigan Historical Publishing Association. The past and Present, Shiawassee County, Michigan, Historically: Together with Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Leading and Prominent Citizens and Illustrious Dead. Durand, MI: Shiawassee County Historical Society, 1982. Print.

Webber, William L. Indian Cession of 1819 Made by the Treaty of Saginaw. Saginaw, MI: Seemann & Peters, 1895. Print.

One Response

Excellent documented history! I have learned quite a bit of the history of the rock and the settlements around here. An excellent article Monte!